Time travel usually belongs to the realm of science fiction. We imagine machines, portals, or distant futures. And yet, in a very real and very human way, nervous system time travel is something we experience every day.

Your nervous system travels through time, it constantly moves between what has been and what might be, often without you noticing. It draws on experience, refines its expectations, and shapes your reactions long before your conscious awareness has a chance to step in. For your nervous system, time is relative and actually, “time” is not even a concept that your nervous system understands or deals with – but we’ll get to that in a minute.

Your triggers are time travelers as well. They rarely respond to what is happening in a purely neutral, present-moment sense. Instead, they arise when the nervous system recognizes a familiar pattern, one that has previously been linked to pain, overwhelm, or threat.

To understand why this happens, it helps to recognize that your nervous system and your conscious awareness relate to time in very different ways. Conscious awareness tends to organize experience linearly: the past is over, the present is now, and the future lies ahead. The nervous system does not work with timelines. It works with patterns.

Rather than tracking when something happened, the nervous system tracks how it felt and what it meant for survival. When an experience is painful, frightening, or overwhelming, the system refines its ability to recognize the pattern associated with that experience. The more intense the original experience, the more finely tuned this pattern recognition becomes.

At first, the pattern may be relatively specific. Over time, however, it often expands. New experiences that are less intense, but emotionally linked to the original pain, get added to the same internal category. A tone of voice, a facial expression, a certain kind of silence, or a familiar sense of pressure can all become part of the pattern. Each additional experience sharpens the nervous system’s sensitivity, making the pattern easier and faster to detect.

From the nervous system’s perspective, this refinement is intelligent. It allows for quicker responses and earlier intervention. The system is not trying to replay the past or predict the future in a conscious sense. It is continuously updating its pattern library to reduce the risk of being caught off guard again.

This is why triggers can seem to appear out of nowhere. A brief comment in a meeting can activate a cascade of sensations that feel far bigger than the moment itself. A neutral email can evoke a sudden sense of dread or urgency. It is not that the nervous system believes the same event is happening again, but that it recognizes a familiar pattern and responds accordingly.

This is nervous system time travel, not in the sense of moving backward or forward along a timeline, but in the sense of responding to accumulated patterns rather than isolated moments.

It is important to understand that this is not a malfunction. It is not weakness, and it is not irrational. It is learning at it’s finest.

We often associate learning with growth, mastery, and expanded capability. Through experience, we learn to read, to write, to create, and to perform complex skills with increasing ease. An athlete trains their body until movement becomes intuitive. An author refines their relationship with language until ideas flow naturally. These forms of learning increase flexibility and choice.

The nervous system also learns through experience, but with a different primary aim. Its focus is protection not growth.

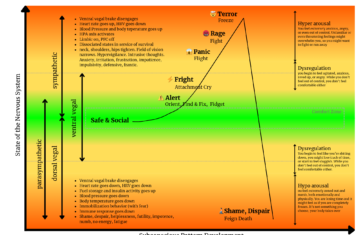

When an experience exceeds what feels manageable at the time, the nervous system adapts. It refines its pattern recognition and builds automatic responses designed to reduce exposure to similar pain in the future. These responses operate beneath conscious awareness and activate quickly, precisely because speed once mattered.

If heightened alertness helped you avoid harm, the system strengthened vigilance. If pleasing others reduced conflict, it refined appeasement. If freezing or disconnecting made an unbearable situation survivable, it reinforced shutdown. Each response was shaped by experience and honed through repetition.

The challenge arises not because these patterns exist, but because they continue to expand and generalize. Over time, the nervous system may respond not only to situations that closely resemble the original experience, but also to situations that share only a few emotional or sensory elements. The threshold for activation becomes lower, and triggering becomes easier.

Meanwhile, conscious awareness may recognize that the current situation is different. You may know that you have more resources now, more choice, and more capacity. Yet this knowledge alone rarely overrides a nervous system that is responding to a well-practiced pattern rather than to a logical assessment.

That is because the nervous system does not respond to explanations about time or context. It responds to what is sensed in the body, and to whether the present moment carries recognizable signals of safety or threat. These signals are not abstract ideas; they are concrete, embodied cues the nervous system has learned to detect with great sensitivity.

So the real question is not how to convince the nervous system that the past is over. From the nervous system’s perspective, that framing does not quite apply. It has no direct sense of past, present, or future. Instead, the question becomes how to gently recalibrate its pattern recognition in the present, gradually and through repeated experience.

This recalibration happens by offering the nervous system new patterning in the present. Not all at once, and not through force, but through consistent exposure to messages of safety. These are moments in which familiar cues appear, yet the expected danger does not follow. The body notices that activation can arise and settle again, that intensity can be felt without escalation, and that connection, choice, or relief are available where threat was once assumed.

Messages of safety can take many forms. They might be a steady breath that naturally slows, a grounded sense of contact with the chair or floor, a calm and regulated tone of voice, or the experience of staying present with discomfort without needing to escape it. They can also be relational, such as being met with understanding rather than judgment, or internal, such as responding to tension with curiosity instead of urgency.

Each of these moments sends subtle but meaningful information to the nervous system. They do not argue with its protective logic; they update it. Over time, the system begins to refine its patterns in a new direction. What once reliably signaled danger becomes less convincing. The threshold for triggering rises, and the range of what feels tolerable slowly expands.

Triggers may still arise, but they lose their immediacy and control. They become signals that can be noticed rather than commands that must be obeyed.

And slowly, without force or argument, the nervous system becomes less preoccupied with scanning for familiar pain patterns and more capable of registering what is actually happening now.

That is not time travel.

That is presence.

And presence is where lasting change begins.