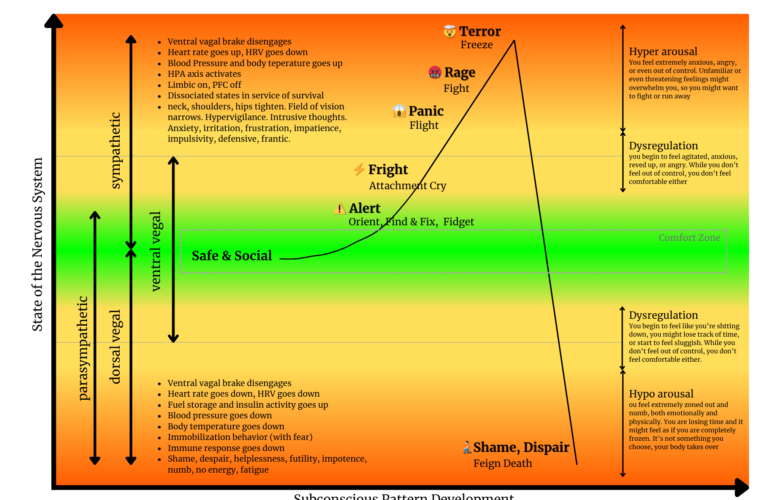

The human nervous system is organized around one primary task: detecting safety or threat and mobilizing the body accordingly. It does not aim for happiness, insight, or even accuracy. It aims for survival. To do this, it continuously shifts between different states of activation. These shifts are largely automatic and shaped by past experiences, not conscious choice.

When regulation is working well, the nervous system moves fluidly between states and returns to a baseline of safety once a challenge has passed. When regulation does not work well, the system gets stuck in heightened activation or collapse, even when no real danger is present. This is what we call dysregulation.

The organizing axis

At the center of regulation is the ventral vagal system. This is the state of safety and social engagement. Here, the body has enough energy to act and enough calm to think. Heart rate variability is high, breathing is flexible, digestion and immune function are supported, and the prefrontal cortex is online. This is where reflection, connection, creativity, and cooperation become possible.

From this regulated baseline, the nervous system can move upward into sympathetic activation or downward into dorsal vagal shutdown. These movements are not pathological in themselves. They are adaptive responses to perceived threat. Problems arise when the system cannot return.

Stage 1: Safe and social regulation

In the regulated state, the nervous system interprets the environment as safe enough. Muscles are relaxed but ready. Attention is open. Emotions are present but tolerable. Other people feel accessible rather than threatening.

This is often described as the comfort zone, not because nothing happens, but because challenges can be met without overwhelming the system. Small fluctuations in arousal are normal and healthy. The ventral vagal “brake” modulates activation up or down as needed.

Stage 2: Alert and orienting

As perceived demand increases, the nervous system gently increases activation. Attention sharpens. The body prepares to act. You may fidget, scan the environment, or feel a subtle sense of urgency.

At this stage, regulation is still largely intact. The person can respond flexibly. This is often where healthy problem solving and focused engagement occur. The system is mobilizing, but not yet in survival mode.

Stage 3: Fright and attachment-driven distress

If the situation feels overwhelming or unpredictable, activation increases further. Emotional intensity rises. The nervous system may seek help, reassurance, or proximity. This can look like agitation, urgency, or an emotional cry for connection.

Cognitively, the prefrontal cortex begins to lose influence. Thinking becomes more reactive. Emotion and body sensation take the lead. Regulation is now strained, but not yet fully lost.

Stage 4: Fight or flight mobilization

When threat is perceived as imminent, the sympathetic nervous system dominates. Heart rate and blood pressure increase. Muscles tense. The field of vision narrows. The limbic system drives behavior.

Fight may express as anger, irritability, defensiveness, or confrontation. Flight may express as anxiety, panic, restlessness, or the urge to escape. In both cases, the system prioritizes action over reflection.

At this level, people often say things they later regret or make decisions that do not reflect their values. This is not a character issue. It is a neurobiological state in which higher reasoning is temporarily offline.

Stage 5: Freeze and terror

If neither fighting nor fleeing feels possible, the nervous system may escalate into a freeze response. This is a high-arousal state combined with immobilization. Internally, the body is flooded with stress chemistry. Externally, the person may appear frozen, disconnected, or unable to act.

This state is often accompanied by terror, dissociation, or a sense of losing control. Regulation is largely absent. The nervous system is now fully in survival mode.

Stage 6: Dorsal vagal shutdown

When threat feels inescapable or prolonged, the system may drop into a low-energy survival strategy. Heart rate and blood pressure decrease. Body temperature drops. Energy collapses.

Psychologically, this is often experienced as numbness, shame, hopelessness, or emptiness. Time may feel distorted. Motivation disappears. This is not rest. It is conservation under perceived threat.

Why dysregulation happens

Dysregulation is not caused by intensity alone. It is caused by the combination of perceived threat and insufficient capacity. Past experiences shape what the nervous system interprets as dangerous. As a result, present-day situations can trigger survival responses even when no real danger exists.

Once dysregulated, the nervous system cannot be regulated through logic alone. Telling someone to calm down, think positively, or choose a better response assumes access to neural resources that are temporarily unavailable.

How regulation works

Regulation is the ability to move back toward the ventral vagal state after activation. This happens through cues of safety, not through force. Safety can be internal, such as slow breathing, grounding, or compassionate self-talk. It can also be relational, such as feeling seen, heard, or accompanied by another regulated nervous system.

Over time, repeated experiences of returning to safety expand the system’s capacity. The same stressors become less destabilizing. The nervous system learns that activation does not equal danger and that recovery is possible.

Why this matters

Understanding these stages reframes behavior. What looks like overreaction, avoidance, aggression, or collapse is often a nervous system doing its best to protect. Regulation is not about eliminating these states. It is about restoring flexibility and the ability to come back.

From this perspective, healing, leadership, emotional resilience, and chronic stress recovery all begin in the same place: not with changing behavior, but with supporting the nervous system’s return to safety.